Age Related Macular Degeneration (AMD): Causes and Symptoms

AMD is a chronic eye disease that affects people over the age of 50, leading to vision loss and even blindness. There are two types: dry AMD and wet AMD, the latter being more severe. Early detection is crucial, as symptoms may not be apparent. In this article you can learn more about risk factors such as genetics, lifestyle and age.

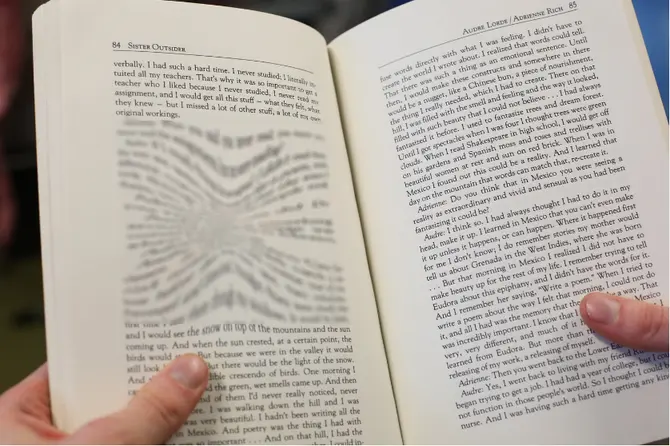

Figure 1. Illustration of central vision loss in people with AMD

Introduction to AMD

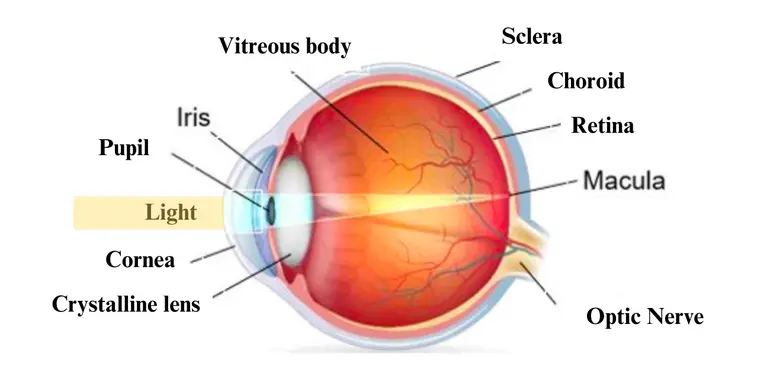

AMD is a chronic, progressive, multifactorial disease that mainly affects people over the age of 50 (1). It is an incurable disease in which vision deteriorates, leading to blindness. During normal vision, light enters the eye through the cornea, passes through the pupil and lens, and converges on the macula at the center of the retina (see Figure 2). When the macula is affected, the individual loses central vision, as illustrated in Figure 1. This loss of vision is often accompanied by difficulties in carrying out activities of daily living, and therefore influences the quality of life not only of those affected, but also of their loved ones.

Figure 2. Anatomy of the human eye

Types of AMD - Wet and Dry Macular Degeneration

There are two types of AMD : dry and wet. Dry AMD is the most common type, accounting for about 80% of all cases. It is characterized by the gradual breakdown of cells in the macula, which leads to a loss of central vision. Wet AMD, on the other hand, is less common but more severe. It is characterized by the growth of abnormal blood vessels under the macula, which can leak and cause scarring and damage to the macula.

Stages of AMD

Early AMD

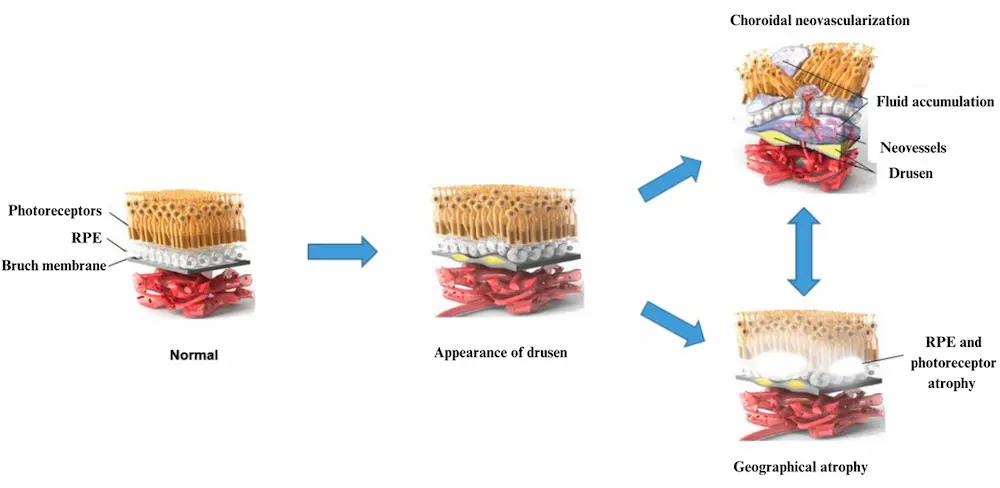

The early, non-degenerative form of AMD, also known as age-related maculopathy (or dry AMD), is characterized by the appearance of small yellowish-white spots called drusen between the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and Bruch's membrane, as illustrated in figure 3. Pigmentary abnormalities of the RPE are also a marker of early AMD, and consist of small hypo- and/or hyper-pigmented areas.

Advanced AMD

Ultimately, early AMD can progress to two advanced forms: atrophic AMD (or advanced dry AMD) and neovascular AMD (or wet AMD). Neovascular AMD is characterized by the proliferation of choroidal neovessels, which are fragile new blood vessels originating in the choroid. These neovessels, which develop through Bruch's membrane as well as under the RPE, allow the diffusion of serum responsible for retinal detachment and/or blood leading to retinal haemorrhages (see Figure 3). The evolution of these neovessels can be slowed by intravitreal injections (i.e., into the vitreous body) of inhibitors of vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), which is a growth factor enabling neovessel formation. However, these injections are not curative, but merely delay the loss of central vision.

Atrophic AMD, on the other hand, is characterized by one or more areas of retinal atrophy, corresponding to the disappearance of RPE cells and photoreceptors (see Figure 3). These atrophic areas gradually enlarge, leading to progressive vision loss. Today, SYFOVRE is the first and only FDA-approved treatment for to treat geographic atrophy (GA), the advanced dry form of AMD.

Figure 3. Visualizing the progression of AMD

Symptoms of AMD - Distorted Vision, Blind Spots, and More

Early symptoms

Early detection of AMD can be difficult, as it often presents no apparent symptoms. That's why it is essential to consult an ophthalmologist for regular screening.

Late symptoms

In the advanced stages, AMD can lead to the appearance of symptoms such as :

- Distortion of objects and straight lines, making them appear wavy or curved

- Decreased visual acuity in the central part of the field of vision, with difficulty in perceiving details.

- Appearance of one or more small dark or black spots (called scotomas) in the center of the field of vision.

- Decreased contrast sensitivity: impression of insufficient light, or of dull or yellowed images.

- Discomfort in night vision.

- Difficulty reading, requiring more light.

- More light.

- Sensation of glare.

- Changes in color vision.

Figure 4. Blurred vision caused by advanced AMD

AMD risk factors

AMD is a complex disease, meaning that several factors such as genetics, lifestyle and environment contribute to its development. These factors can be classified into two broad categories: modifiable and non-modifiable.

Modifiable risk factors

Smoking is the most important modifiable risk factor for the development and progression of advanced AMD. Indeed, current smokers have a two- to three-fold higher risk of developing advanced AMD than non-smokers. These studies also show that former smokers have a lower risk of developing advanced AMD than current smokers, although their risk remains higher compared to non-smokers.

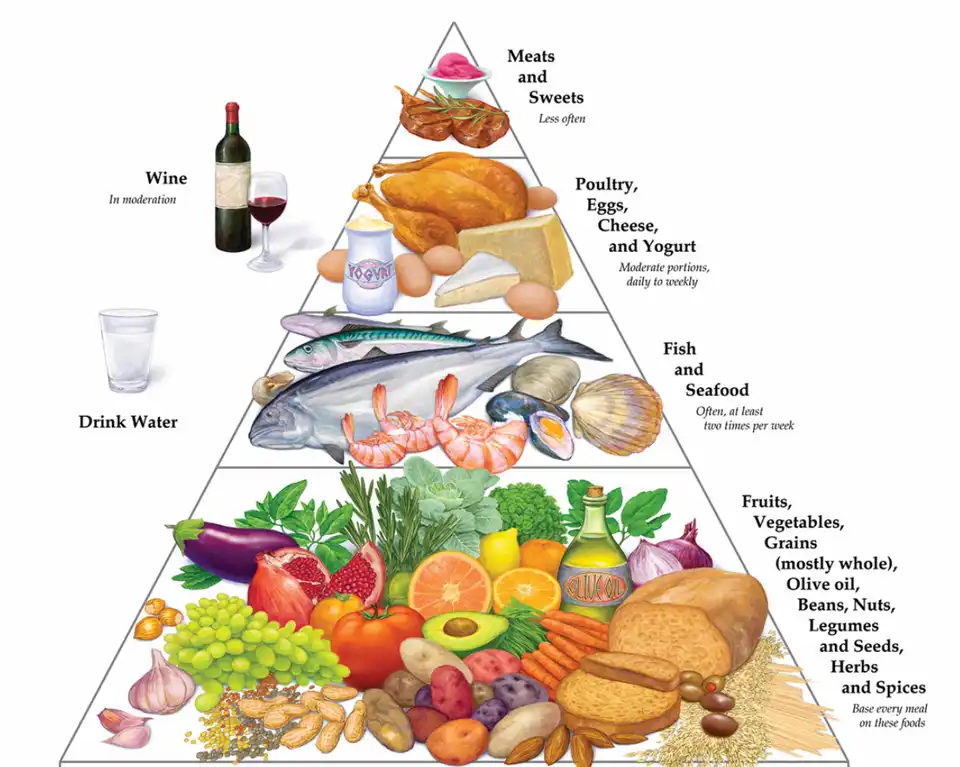

Nutrition also plays an important role in reducing the risk of AMD, particularly the Mediterranean diet, which is characterized by a high intake of vegetables, legumes, fruits, nuts, cereals, fish and olive oil, and a low intake of saturated fats, dairy products, meat and poultry, and regular but moderate alcohol consumption (mainly wine with meals), as illustrated in figure 4. Indeed, high adherence to the Mediterranean diet has been associated with an approximately 40% reduction in the risk of advanced AMD in several studies.

Figure 5. Mediterranean diet pyramid

Other factors such as cataract surgery, high body mass index, low physical activity, sun exposure, high blood pressure and diabetes have been associated with an increased risk of AMD.

Non-modifiable risk factors

As its name suggests, age is the most important non-modifiable factor associated with the development of AMD, and is associated with a strong increase in the prevalence and incidence of this disease. A low level of education has also been associated with an increased risk of AMD. Interestingly, gender is not significantly associated with the development of AMD, as shown in numerous studies.

The involvement of genetic predisposition in the development of AMD was first investigated by family aggregation studies and twin studies. In a US study of 840 twins, the hereditary component of AMD was estimated at between 46% and 71%. These results are consistent with those obtained in family aggregation studies, which reported a higher prevalence of AMD in first-degree relatives of cases compared with controls. This indicates that genetic predisposition plays an important role in the development of AMD.

Epidemiology of AMD

AMD is currently the leading cause of blindness in industrialized countries.

A study published in the prestigious journal The Lancet estimates that 196 million people worldwide had AMD in 2020, and that this number will rise to 288 million by 2040, due to the aging of the world's population.Indeed, the prevalence of AMD increases exponentially with age from the age of 50 onwards, reaching one in two people after the age of 80.

Importance of Regular Eye Exams for AMD Prevention

The most important step you can take to prevent AMD is to get regular eye exams. This can help detect the disease in its early stages, when it is most treatable. If you are over the age of 50, it is recommended that you get a comprehensive eye exam at least once every two years.

Figure 6 Consultation with an ophthalmologist

Conclusion

Age-related macular degeneration is a common eye condition that affects millions of people worldwide, particularly those over the age of 50. It is a leading cause of blindness in industrialized countries. Various risk factors, both modifiable and non-modifiable, contribute to the development and progression of AMD. As the population ages, the prevalence of AMD is expected to increase significantly. Regular eye exams are essential for early detection and timely intervention. By prioritizing regular eye exams, you can take proactive steps in preventing and managing AMD.

To learn more about how you can act on the modifiable risk factors such as nutrition to prevent AMD, you can visit www.macutest.com where you can have access to personalized lifestyle recommendations tailored to your real needs.

Bibliography

- Wong WL, Su X, Li X, et al. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2014.

- Mitchell P, Liew G, Gopinath B, Wong TY. Age-related macular degeneration. Lancet 2018.

- Mitchell J, Bradley C. Quality of life in age-related macular degeneration: a review of the literature. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2006.

- « What Is Macular Degeneration ? » , American Academy of Ophthalmology, 6 avril 2023.

- de Jong PTVM. Age-Related Macular Degeneration. New England Journal of Medicine 2006;355(14):1474–85.

- Chakravarthy U, Harding SP, Rogers CA, et al. Alternative treatments to inhibit VEGF in age-related choroidal neovascularisation: 2-year findings of the IVAN randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2013;382(9900):1258–67.

- Grunwald JE, Daniel E, Huang J, et al. Risk of geographic atrophy in the comparison of age-related macular degeneration treatments trials. Ophthalmology 2014.

- Chew EY, Clemons TE, Agrón E, et al. Ten-year follow-up of age-related macular degeneration in the age-related eye disease study: AREDS report no. 36. JAMA Ophthalmol 2014.

- Sunness JS, Gonzalez-Baron J, Applegate CA, et al. Enlargement of atrophy and visual acuity loss in the geographic atrophy form of age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 1999.

- « FDA Approves SYFOVRE (pegcetacoplan injection) as the First and Only Treatment for Geographic Atrophy (GA), a Leading Cause of Blindness | Apellis Pharmaceuticals, Inc. »

- « Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD) » , Johns Hopkins Medicine, 8 août 2021.

- DeAngelis MM, Owen LA, Morrison MA, et al. Genetics of age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Hum Mol Genet 2017.

- Fritsche LG, Fariss RN, Stambolian D, Abecasis GR, Curcio CA, Swaroop A. Age-related macular degeneration: genetics and biology coming together. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 2014.

- Lim LS, Mitchell P, Seddon JM, Holz FG, Wong TY. Age-related macular degeneration. The Lancet 2012.

- Delcourt C, Diaz JL, Ponton-Sanchez A, Papoz L. Smoking and age-related macular degeneration. The POLA Study. Pathologies Oculaires Liées à l’Age. Arch Ophthalmol 1998.

- Velilla S, García-Medina JJ, García-Layana A, et al. Smoking and age-related macular degeneration: review and update. J Ophthalmol 2013.

- Neuner B, Komm A, Wellmann J, et al. Smoking history and the incidence of age-related